How Long Does It Take Your Brain To Repair Itself After Using Antidepressant Drugs

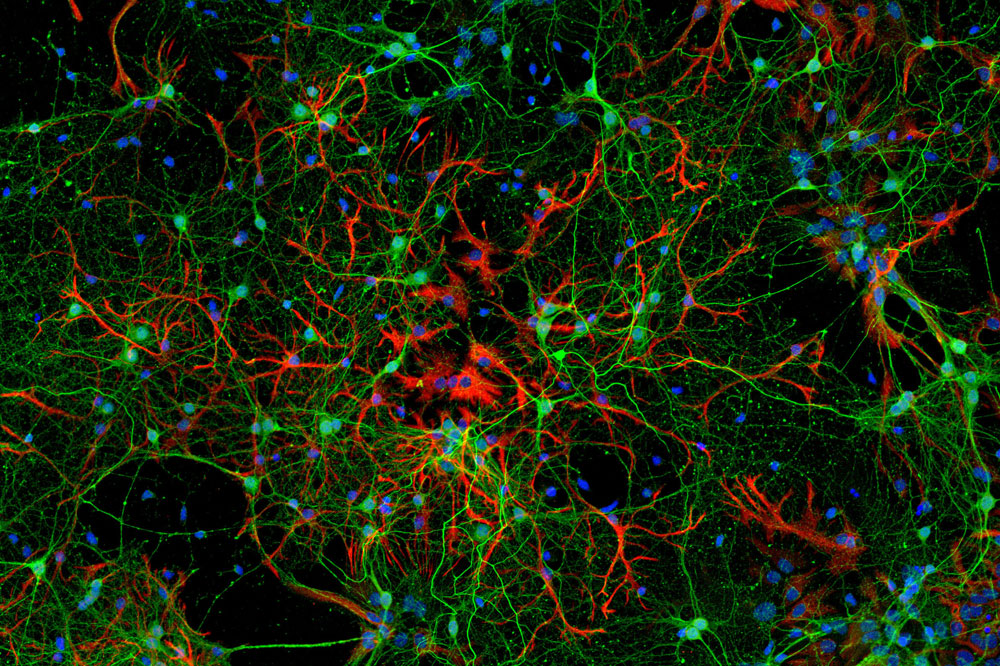

Mouse cortical neurons used to study the molecular response to antidepressant treatment (dark-green) surrounded by astrocytes (red).

Some highly effective medications also happen to exist highly mysterious. Such is the case with the antidepressant drugs known as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, or SSRIs: They are the well-nigh common handling for major depression and have been around for more than than forty years, all the same scientists still do not know exactly how they work.

Nor is it known why merely two out of every iii patients respond to SSRI treatment, or why it typically takes several weeks for the drugs to take upshot—a significant shortcoming when yous're dealing with a disabling mood disorder that can lead to dumb sleep, loss of ambition, and fifty-fifty suicide.

New research by a team of Rockefeller scientists helps elucidate how SSRIs gainsay depression. Their work, published in Molecular Psychiatry, could one day brand it possible to predict who will respond to SSRIs and who will non, and to reduce the corporeality of fourth dimension information technology takes for the drugs to human action.

Brain Teasers

Major depression—also known as clinical depression—is firmly rooted in biology and biochemistry. The brains of people who suffer from the disease testify low levels of certain neurotransmitters, the chemic messengers that allow neurons to communicate with one some other. And studies have linked low to changes in brain volume and dumb neural circuitry.

Scientists accept long known that SSRIs quickly increase the bachelor amount of the neurotransmitter serotonin, leading to changes that become well beyond brain chemistry: Inquiry suggests the drugs assist reverse the neurological damage associated with depression by boosting the brain's innate power to repair and remodel itself, a feature known as plasticity. Withal the molecular details of how SSRIs work their magic remains a mystery.

Researchers in the belatedly Paul Greengard'south Laboratory of Molecular and Cellular Neuroscience set out to trace the chain of molecular events triggered by i of the most widely prescribed and constructive SSRIs: fluoxetine, also known equally Prozac. In particular, they wanted to see if they could necktie the effects of the drug to specific changes in cistron expression.

Led past senior research associate Revathy Chottekalapanda, the squad treated mice with fluoxetine for 28 days, and so measured the animals' biochemical and behavioral responses to the drug. They conducted these experiments in a mouse strain prone to anxiety that offered several advantages including the fact that "improvement in feet, in add-on to depressive-like beliefs, is a good measure out of antidepressant drug response," Chottekalapanda says.

Using a combination of behavioral tests and real-time RNA analysis, the researchers were able to monitor changes in the animals' behavior and gene expression equally they responded to the drug. Things started to get interesting on the 9th day of treatment: The activity of a gene chosen c-Fos began to increase markedly, and by day 14 the mice were showing telltale behavioral changes—they were moving effectually more, for instance, and took an interest in food even afterwards being moved to a new environment. The timing was remarkable, Chottekalapanda says, because it aligned with well-established milestones in the handling of human being patients.

"For example, the rate of suicide drops after nine days of treatment, and people tend to feel better after two to three weeks," she says.

As it turns out, c-Fos helps create a then-chosen transcription factor, AP-one, which activates specific genes by binding to their DNA. The sudden appearance of these molecules therefore raised several new questions: Which genes does AP-1 actuate? What triggers the production of AP-1 in the first place? And how does this whole sequence of events ultimately beat back low?

Domino Effect

Chottekalapanda and her colleagues began by analyzing the mice'southward cortex, a brain region previously shown to be essential for the antidepressant response, looking for changes in genes and DNA-binding proteins to which AP-1 might peradventure bind. Focusing peculiarly on the nine-solar day mark, they constitute changes in mouse genes whose homo counterparts have been linked to depression and antidepressant drug response.

Walking the true cat backward, the squad was able to identify specific molecules known as growth factors that spur the manufacture AP-1 itself, and the pathways through which they act. Taken together, these results painted a detailed moving picture of how fluoxetine and other SSRIs work.

First, the drugs ramp upwardly the amount of serotonin available in the brain. This triggers a molecular concatenation reaction that ultimately makes brain cells increment their AP-1 production—an effect that simply begins to have off on day nine of treatment. AP-1 then switches on several genes that promote neuronal plasticity and remodeling, assuasive the brain to contrary the neurological damage associated with low. After two to iii weeks, the regenerative effects of those changes can exist seen—and felt.

"For the kickoff time, we were able to put a number of molecular actors together at the criminal offence scene in a time- and sequence-specific manner," says Chottekalapanda.

To confirm their molecular model of SSRI response, Chottekalapanda and her team gave mice treated with fluoxetine an boosted substance designed to block i of the pathways necessary to the product of AP-1.

The results were striking: When the researchers prevented the mice from producing AP-1, the effects of the drug were severely blunted. Moreover, gene-expression assay showed that blocking the germination of AP-ane partially reversed the activation of some of the genes responsible for the antidepressant response.

I Word: Plasticity

The implications of the team's findings could be far-reaching. For example, the genes that AP-i targets could be used every bit biomarkers to predict whether a given patient volition reply to SSRI treatment. And the cast of molecular characters involved in fluoxetine response could potentially be targeted with drugs to improve the efficacy of antidepressant treatment, mayhap fifty-fifty reducing the amount of time it takes for SSRIs to kick in.

Towards that stop, Chottekalapanda is already conducting experiments to clarify the precise reasons for the ix-day delay in AP-1 product. She would also like to know whether these molecular players are mutated or inactive in people who don't reply to SSRIs, and to discover precisely how the genes that AP-1 regulates in response to fluoxetine would promote neuronal plasticity.

That final slice of the puzzle might prove to be particularly important. Low is not the merely disorder that could potentially be remedied by enlisting the brain's innate healing abilities: Chottekalapanda suspects that the same plasticity-promoting pathways that are activated by antidepressants such as fluoxetine could potentially be used to treat other neurological and neurodegenerative conditions such as Alzheimer's and Parkinson's disease.

"If nosotros can figure out what they do, we tin can potentially develop treatments to contrary the damage involved not only with depression but also with other neurological disorders," she says.

Source: https://www.rockefeller.edu/news/28742-study-unveils-molecular-events-popular-antidepressants-work/

Posted by: fowlerthavest.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How Long Does It Take Your Brain To Repair Itself After Using Antidepressant Drugs"

Post a Comment